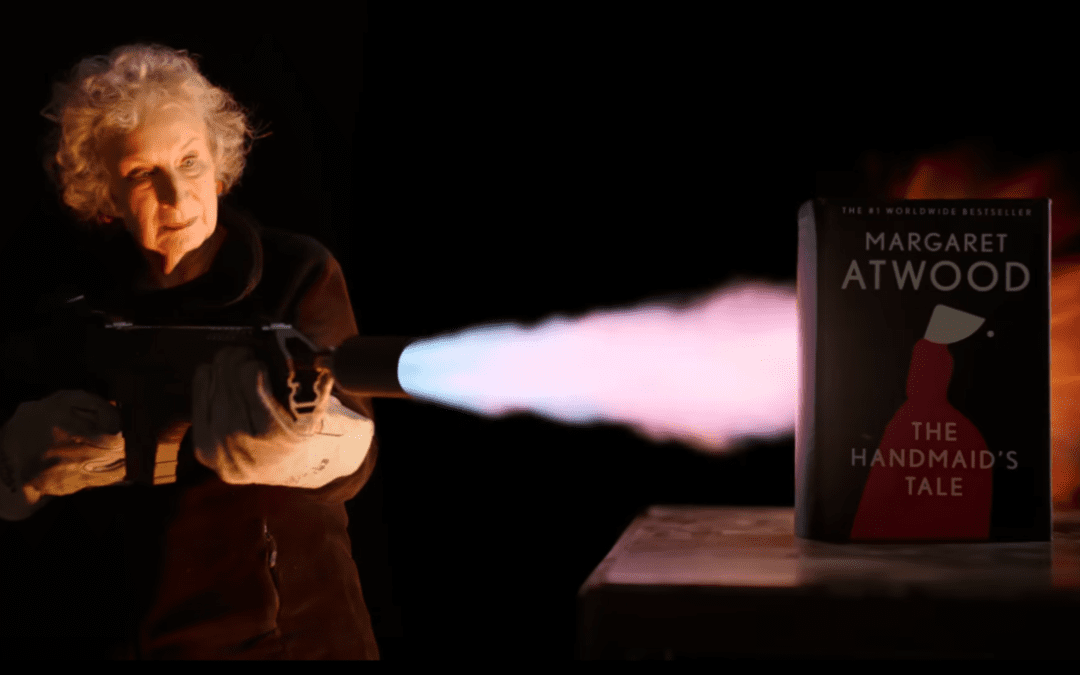

In the wake of ongoing issues of censorship in schools in America, author Margaret Atwood has teamed up with Penguin Publishing to release a one of a kind unburnable edition of her award-winning novel, The Handmaid’s Tale. In the last decade, The Handmaid’s Tale was in the top 30 most challenged books in American schools and libraries.

The special edition of the novel is being auctioned to the public with all proceeds going to PEN America, a group that “works to ensure that people everywhere have the freedom to create literature, to convey information and ideas, to express their views, and to access the views, ideas, and literature of others”.

The issue of literary censorship has again reared its head in America with The New York Times reporting “ … parents, activists, school board officials and lawmakers around the country are challenging books at a pace not seen in decades.”

In 2020, there were 156 challenges to library, school, and university materials and services. This number rose significantly to 729 in 2021 highlighting a distinct shift in national sentiment. To put this in context, Australia has banned 416 novels in total, with the majority now unbanned.

In Australia, books may be banned due to racial issues, encouragement of “damaging” lifestyles, blasphemous dialogue, sexual situations or dialogue, violence or negativity, presence of witchcraft, religious affiliations, political bias and age appropriateness. These categories, however, are only guides for what a book may be banned under. Books that are challenged are reviewed and the burden of proof lies with the person who is making the challenge. This means that whilst the criteria for books being banned remain the same as it has throughout history, challenges are considered within the culture of the time it has been challenged. This is why we see many books unbanned, as content that was previously offensive becomes more accepted.

UOW Head of the Bachelor of Creative Arts academic program and English literature senior lecturer Dr Joshua Lobb said banning books does not remove their ideas from public consciousness and discussion.

“The idea of banning things because they don’t support a worldview doesn’t mean the worldview isn’t going to be there,” Dr Lobb said.

“By banning something you make it more powerful because you make people want to think about it more intensely and they don’t have all the information.”

Dr Lobb said representation was important in literature because it can be used to enforce particular worldviews.

“In the past, there has been banning of particular political worldviews and there has been the shaping of Australian history or gender or sexuality, they can be damaging to people because they can feel that they are not represented in the text,” Dr Lobb said.

“The implications of banning means that people aren’t going to have all the opportunities to understand how the world can be.”

Full interview: Dr Joshua Lobb

Dr Lobb said a system that relied on guidance, like that in place now, was better than book bans.

“It’s about making sure people have a conversation about things, there are ways in which we need to allow people to think through what they want to do and what they want to read,” he said.

“But at the end of the day, there will always be ways for people to find the books they want to find.”

Classic Books Banned Internationally by UOWTV

Feature image; Penguin Random House