Content warning: this story contains discussion of colonial violence and other themes that may be distressing to First Peoples of Australia.

The New South Wales Government announced in 2015 it planned to relocate the Powerhouse Museum to Western Sydney. The backlash and controversy snowballed and stirred community members against the government’s plans.

Not long after the NSW Government announced the relocation, it went public with its plan to develop a site on Phillip St in Parramatta’s Central Business District. The government didn’t have its eye on any ordinary plot of land. It planned to develop a lot located next to the Parramatta River. The land houses two heritage buildings from the late 1800s: an Italianate villa, Willow Grove, and St George’s Terrace.

Willow Grove and the land it is built on hold significant value to the Dharug people and other community members for personal, historical, cultural, and environmental reasons. This significance drove Western and Greater Sydney residents from diverse backgrounds and organisations to collaborate after the announcement. Together, they fought for the next four years to preserve the two buildings and the land itself.

The fight for Willow Grove

At the centre of the movement against the NSW Government and private developers, organisations like the North Parramatta Residents Action Group (NPRAG) and the Dharug Strategic Management Group (DSMG) took the fight into their own hands.

Suzette Meade, NPRAG Secretary, said that her and the action group became involved because the community was being ignored. In 2016, when the government announced the development, NPRAG formed an alliance with the campaign group Save the Powerhouse.

“I really threw myself into this. In the last two years, it became a full-time job for me, which is probably the success of the campaign because I worked on it full-time. On the phone eight hours a day, going to Upper House inquiries, meeting members of parliament, meeting unions, meeting like-minded communities and heritage organisations,” Meade said.

In 2020, the Berejiklian government opened submissions to show objection or support of the development from individuals, organisations, and public authorities. In this round of submissions, 1222 individual people submitted their objections to the development, whilst 26 people supported it. In the second round of public submissions, 360 people objected and one person supported the construction of Powerhouse Parramatta on the site.

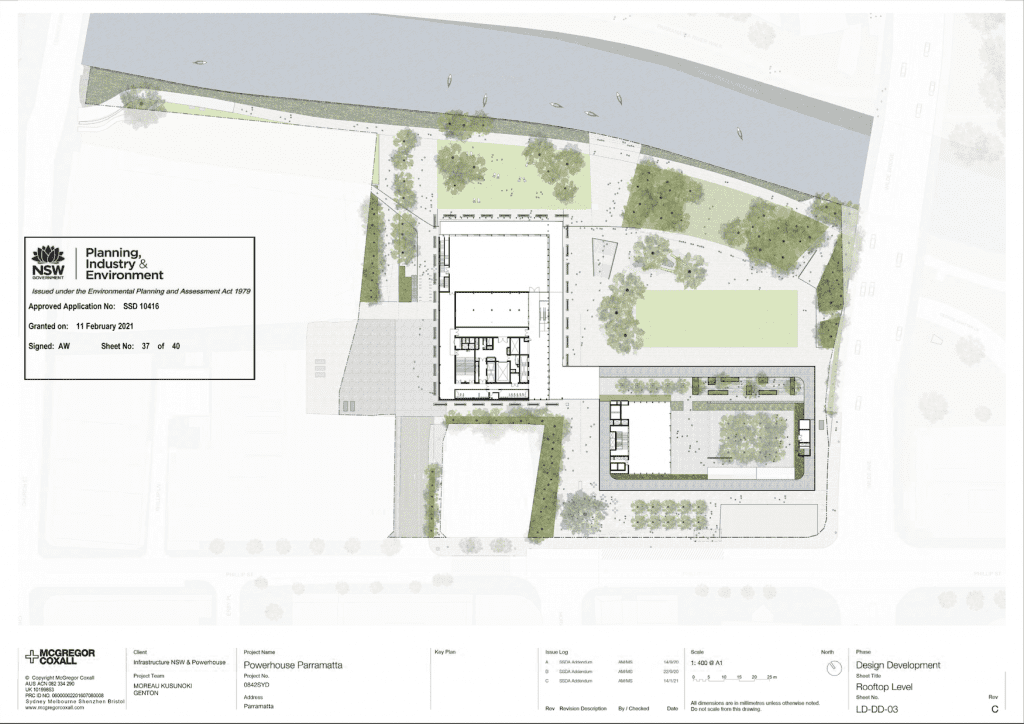

Source: NSW Government, rooftop level Powerhouse Parramatta.

Councillor Donna Davis was elected to Parramatta City Council in 2017. She started work on the campaign when the community became increasingly concerned for the future of the site and its buildings. Like Suzette Meade, Clr Davis dedicated much of her time and energy to the campaign.

“The way it happened was that it was very organic. Like for anything to succeed, you have to have people that are committed and at the core. Really for the entire period Suzette and I have been that core,” the councillor said.

Source: NPRAG, Councillor Donna Davis attends a demonstration.

“I was really worried. So were a lot of people in the community about what [the development] would mean for Willow Grove, but we felt confident that given it was a government development, given the significance of Willow Grove, its age, that of St George’s Terrace as well, we felt that we would be able to save the building and it would become a part of that whole redevelopment of that site.”

Organisers created a campaign that incorporated their dedication and personal connections to Willow Grove and its story into their fight.

“We had a Valentine’s Day event, and we painted all these timber hearts and people would come and write their name on it and tie the heart on the fence,” Meade said.

When the first COVID-19 NSW lockdown started one month later, campaigners took their actions online. After restrictions eased, a group of artists, knitters, and community ‘love bombed’ Willow Grove and St George’s Terrace, decorating the site as well as cleaning it.

Alec Zammitt helped organise the event with his culture and community-focused group Craze Collective.

“We spoke with a few other local artists and if they weren’t already aware of what was happening there, we showed them the information and let them know the state of affairs that the buildings were in at the time,” he said.

In the early days of its campaign, NPRAG tried to engage with Parramatta City Council to stop the proposal. After the strategy fell through and the NSW Government pressed forward, the organisers began discussing a green ban.

“I felt that if anything was going to help us save Willow Grove, it would be the green ban,” said Clr Davis.

“It gave us an incredible sense of connection to a much broader community. This really showed the support and interest and that we were actually fighting a fight that so many people believed in.”

The campaign to save Willow Grove and St George’s Terrace shared similarities with past heritage movements. Some campaigners involved drew parallels to the work of Jack Mundey.

In 1970s Sydney, Mundey and other union officials led the Builders Labours Federation (BLF) members on green ban action across NSW and other parts of Australia. Their work to save heritage sites such as The Rocks and Centennial Park in Sydney City set a precedent and legacy that continues to inform union and community campaigning despite the BLF no longer existing.

The NSW Branch of the Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU) joined the campaign and in June 2020, it placed a green ban on Willow Grove and St George’s Terrace. The CFMEU created the petition, Support the Green Ban on Parramatta Heritage Sites, which gained 5,722 signatories.

“These Green Bans [sic] mean no work can be done to destroy these historically significant sites,” CFMEU NSW Secretary Darren Greenfield said in a public statement announcing the union’s intervention.

“If the Berejiklian government wants work on the museum to proceed they need to sit down with the local community, listen to what they say and come up with a plan that preserves these buildings.

“The local community, through the North Parramatta Residents Action Group, has campaigned for years to save these two heritage buildings and they are supported by the National Trust of Australia (NSW) and the Historic Houses Association.”

Once the CFMEU placed a green ban on the site in 2020, tensions increased over the next year between organisers and the NSW Government. In 2021, NPRAG initiated legal action to save the land and heritage buildings.

“Unfortunately, we couldn’t go to the Supreme Court [in person] because of COVID-19 restrictions,” Meade said.

“But we did start out with the Land and Environment Court. That was where we took Infrastructure NSW and the planning minister, we served them notices. My heart was racing because I meet the planning minister quite regularly on other matters.”

When NPRAG challenged Infrastructure NSW earlier in the year, they argued its Environmental Impact Statement “failed to consider any alternative site” to locate the Parramatta Powerhouse development.

The North Parramatta Residents Action Group made an appeal to the NSW Supreme Court on 2 July. While the court heard the group’s appeal, an injunction was placed on the site to stop any work on Willow Grove. After the court announced the injunction, NPRAG said that community members would remain vigilant. This included some volunteers who kept watch overnight in case construction workers entered the premises against the ruling.

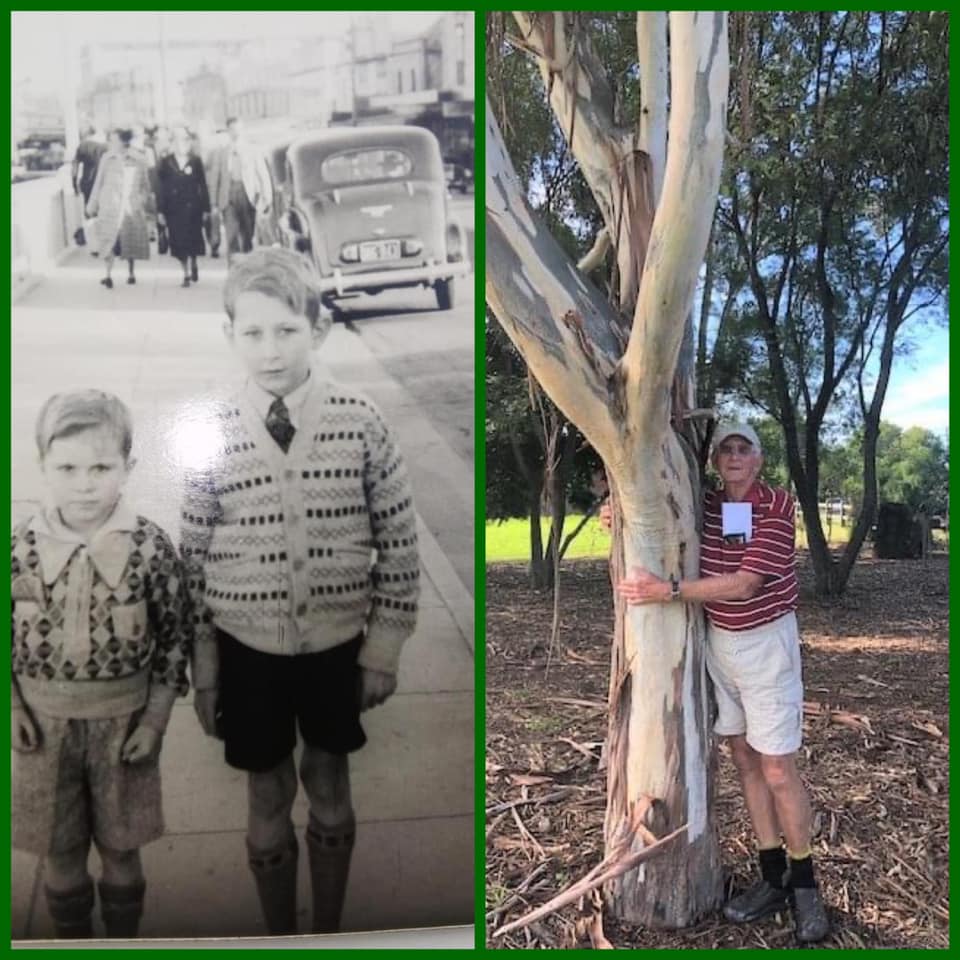

Source: NPRAG, Left: Keith Steele and sibling. Right: Steele at Sue Savage Reserve, Toongabbie, next to one of the trees he planted rehabilitating the area. Steele was one of the thousands of residents born at Willow Grove when it was a maternity hospital.

Lockdown stymies campaign action

Organisers adapted to coordination online throughout the first COVID-19 lockdown and once restrictions eased, things returned in person. This was the case until the next lockdown, starting on 16 June 2021, stopped the campaign in its tracks again. Restrictions tightened once more days after the CMFEU announced its Willow Grove green ban. The Delta COVID-19 strain put life on hold for residents and meant that no one involved with the campaign could organise in person against the development.

In the first week of August, the Berejiklian State Government said from 11 August, the construction industry would operate at 50% to help “sustain industry, boost the economy and keep workers safe.”

On 24 August, the CFMEU lifted its green ban after maintaining it for two months in lockdown. The union’s decision came off the back of mounting pressure within the construction industry for a return to work.

The NSW Government released a statement after the union’s announcement to lift the green ban. NSW Minister for the Arts Don Harwin, along with Museum Trust President, Peter Collins AM QC, and Powerhouse Chief Executive Lisa Havilah, welcomed the end to the union’s intervention.

“The Government is looking forward to announcing the main contractor for the construction of the Powerhouse Parramatta in the near future,” Mr Harwin said.

“Powerhouse Parramatta will be the first State cultural institution in Western Sydney. It will be a magnificent science and technology museum that will delight families and greatly contribute to the Parramatta community.”

NPRAG accused the Berejiklian government of using “the Covid Crisis to start the desecration of the Willow Grove site.” During this time, COVID-19 cases rose in Western Sydney LGAs and strict lockdown measures were imposed on the area, including a curfew. A controversial increased police presence was also introduced.

Days after the decision and following two months of remote campaigning, Suzette Meade spoke to over 100 delegates from the CFMEU’s NSW branch in an online conference. In her speech, Meade reflected on lockdown difficulties and its blow to the campaign, which resulted in the green ban lifting.

“We are certain that if the NSW Premier had not mismanaged the pandemic response that you would all be standing with the community today arms linked protecting Willow Grove. The CFMEU and community put up a significant fight and that is a historical achievement. The State Government knew what they were up against and ruthlessly took the opportunity COVID presented,” Meade said in her speech.

When asked about feelings on the green ban lifting, Suzette Meade said, if given the chance, organisers and demonstrators would take greater action against the NSW Government.

“This was going to come down to combat,” Meade said.

“The letdown now is we didn’t get to go to combat. Even if we’d lost at combat, we would have gone out fighting.

“I was going to make sure I wore trousers, and I was going to be carried off like Jack Mundey, by all fours, smirking away.”

“Darren Greenfield said to me, when I spoke to the delegates, after they pulled out of the green ban, he said, ‘Suzette I was going to chain myself to the internal timber stairs’, he said. ‘I had it all worked out’. And I said, ‘I was going to make sure I wore trousers, and I was going to be carried off like Jack Mundey, by all fours, smirking away.’

Source: ANU Archives, photographer Robert Pearce, Sydney Morning Herald.

“For it to stop without a climax feels like it’s unfinished business.

“I’m feeling very empty and unresolved. Since the CFMEU lifted the green ban, it has left a lot of time for reflection and, I guess, debriefing a lot of groups that were involved.”

On 11 October, Clr Davis posted a video to her Facebook page. In the video, construction fencing and scaffolding obscures the view of Willow Grove. Clr Davis’ caption read: “This is Willow Grove packed up on crates ready to be trucked off to storage.” At the time the post was published, the NSW Government had not made a public proposal or undertaken any serious consultation to relocate and build their promised replica.

Public comments from community members on the post expressed disapproval, with some suggesting the museum’s design could have incorporated the heritage site. Clr Davis wrote in the caption: “Parramatta Powerhouse has been redesigned for flooding [and] to include St George’s Terrace, but the NSW Govt. refused to incorporate Willow Grove.”

The history of Willow Grove

Press play to hear about the site’s story and importance.

Development ignores Dharug voices

All throughout Australia, many colonial buildings and sites echo settler violence against First Nations. When settlers entered the Parramatta area in 1798 they introduced smallpox, which is estimated to have killed up to 90% of the Dharug population. While Willow Grove is a settler-colonial building and still a product of this time, it stands out from other Parramatta colonial buildings. This is because Annie Gallagher, who purchased the land in 1891, gave Dharug people access to the land and river.

Dharug woman and DSMG Chair Julie Jones says she grew up hearing the oral history on Country from her family and that it is vital for people to understand the connection between the Dharug people and Nura (Place).

“Annie Gallagher used to allow our people when we came back into Barramadda,” Jones said.

“Because we were pushed to the fringes when the settlement was in the early days. When we started to come back, Annie Gallagher really offered that hand of reconciliation and allowed our people, apparently, to access the river for purposes of fishing and cultural practices.

“I’ve always had a great love for Willow Grove. So, it was very important for us to get the story in there. With our cultural heritage disappearing all over the place, we need to step up and voice those concerns and make sure that people know our story of Place.”

When the Berejiklian government exhibited its Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to the public from June to July in 2020, the Dharug Strategic Management Group submitted a response. In its statement, the group said the government had not done enough to consider their concerns as First Peoples of Australia.

“DSMG feels complete and utter dismay that the EIS continues a long record of NSW Government failure to recognise, respect and value Dharug stories of being, belonging and becoming within the Parramatta district or the site that is directly affected by the construction of the MAAS facility,” the group’s statement said.

“Unlike most colonial heritage buildings in Parramatta, [Willow Grove] holds no history of colonial violence, incarceration and denial of Dharug people and our neighbours. Rather, Willow Grove reflects a shared history of care and nurture. Its wilful destruction as part of the Powerhouse at Parramatta project reinscribes the historical trauma inflicted on Dharug yura that occurred in previous eras of colonial occupation.

“All the design and landscaping decisions, funding and planning arrangements were already in place before any meaningful consultation occurred and the project’s Community Reference Group has been presented with a fait accompli rather than an opportunity to be heard.”

The statement also condemned the State Government for “treating the Nura as ‘terra nullius’”. The DSMG compares the government’s lack of consultation with First Peoples of Australia to colonialist views that “see banks as a place waiting to be conjured into existence as something worth owning (or visiting).”

Parramatta City Council made a submission on the development and included its meeting minutes on 18 June. In the meeting, the council raised several issues that include: the proposal did not consider the retention and incorporation of Willow Grove and St George’s Terrace into the design; refutation that the heritage loss had “minor culminative impact”, and that the project originated during the administration of the council and didn’t allow for an “elected voice.”

“The site sits on the millennia-old state significant Parramatta sand body (also known as the sand-shelf) which is testament and preserves the archaeological record of the occupation of this land by Aboriginal people for at least thirty thousand years,” the council meeting minutes stated.

Despite the issues presented, Parramatta City Council gave its support to the development during submissions to Infrastructure NSW. In its submission, the council “asked” that the NSW Government be “collaborative” and consider the material presented in minutes.

Julie Jones said Powerhouse representatives went to a government inquiry on the development and stated that they had consulted the Dharug Strategic Management Group on the project.

“To have people from the powerhouse, go into the government inquiry and actually say that they’d recently consulted with us, [that] was an absolute fabrication,” Jones said.

“We had to actually write away for a correction to the Hansard. Those kinds of things make it really difficult for a sovereign people that aren’t acknowledged by a lot of government and aren’t acknowledged by either of the land councils that sit on our Country.

“We’ve been very let down, as a community of sovereign people, in regards to all the decision making processes and how that’s been handled. And we do feel that there’ve been a genuine lack of transparency in information that’s coming back and forward.”

Jones said she struggles to understand why the plans went ahead despite the public backlash against the development of the riverside land. Jones supported the idea of a Powerhouse site in Parramatta but said that the bank “wasn’t that space.”

Finding the way forward

For the people who have dedicated time to Willow Grove, there’s mixed feelings about the next steps. While it’s a disappointment to organisers, they’ve also said that some “positives can be taken away” from the campaign.

“There [were] some brilliant minds, some brilliant historians, some amazing, incredible human beings that fought for that place. And we know that we can take those people and those minds and those thoughts and those processes and that passion and we can move that onto our next project,” Jones said.

Clr Donna Davis said, for many people, it was the first time they’d been involved in community action. Earlier in the year, the union movement decided to move its May Day march to Parramatta from its usual route in Sydney.

Clr Davis and Suzette Meade both took the opportunity to raise public awareness about their campaign. Clr Davis said people believed it couldn’t be moved to Parramatta, but that the decision to hold it there reflected why it was “such an important fight.”

Suzette Meade said, from here, after the campaign’s end, she wants to maintain the momentum picked up from trying to save the site.

“We need to keep this fire burning,” Meade said.

“We need to maintain the rage. I think what’s really important is we actually did have a win. We saved seven terraces.

“We forget that because Willow Grove was the jewel. But we actually forced the government to make a lot of concessions from what we did. We need to make sure we own the narrative of this now. That this whole battle is our battle. It’s our fight. It’s our loss.”

Feature image: Courtesy North Parramatta Residents Action Group.