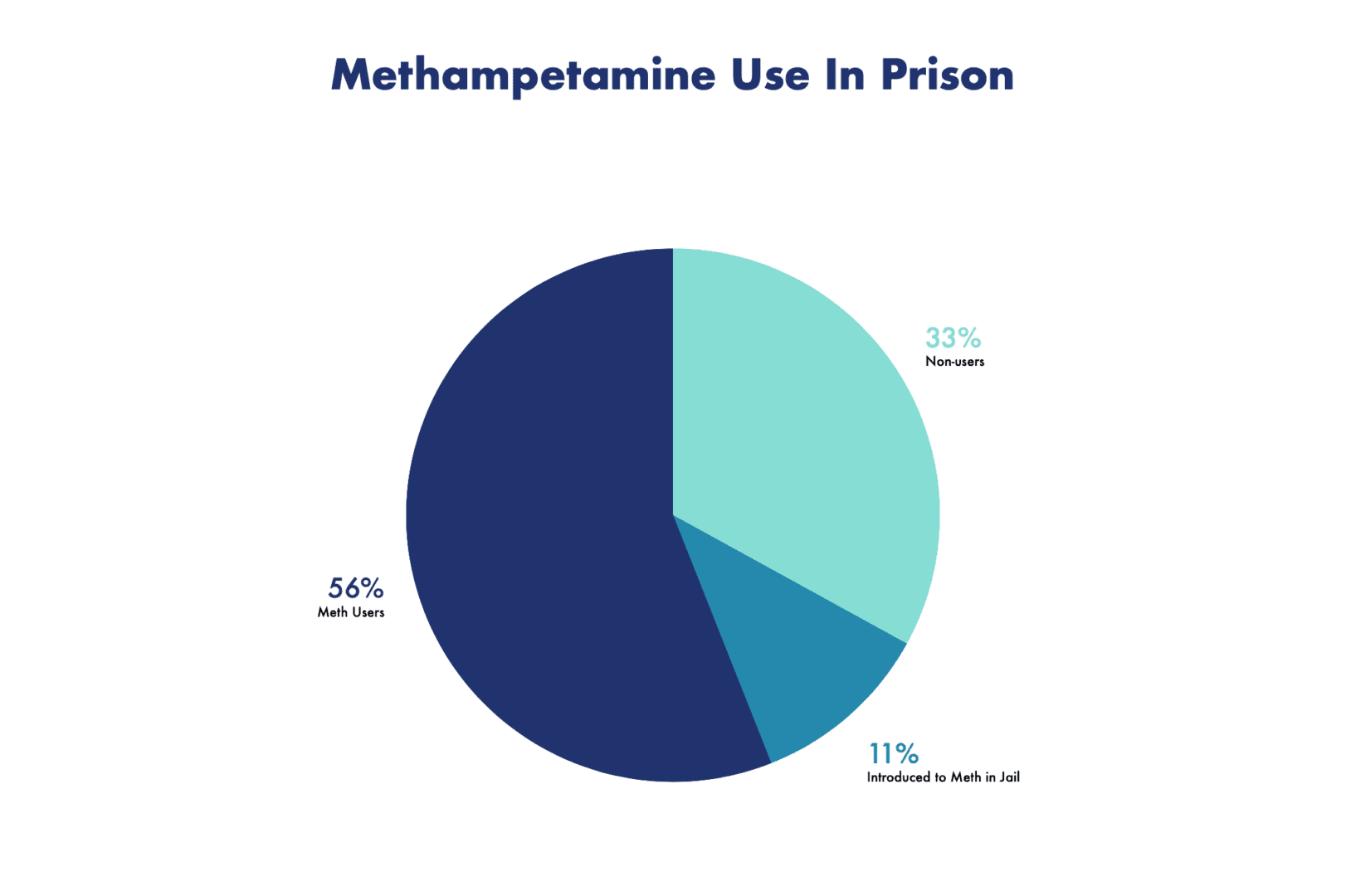

A recent government inquiry into methamphetamine has revealed that as many as two thirds of NSW prison inmates were using meth.

The inquiry, which sat in Sydney, heard evidence of the methamphetamine pandemic that is currently effecting Australia. Among the most troubling evidence was the reports that around 56% of the prison population had been using meth before they were incarcerated with a further 11% being introduced to meth whilst in prison. What’s more, these numbers are likely to be underestimated.

The inquiry painted a troubling image of the impact that meth is having upon our prison system and its inability to cope under the current procedures.

These statistics can be attributed to a multitude of issues that result in a ‘revolving door’ effect where users are often forced into crime due to their meth addiction, and then are able to continue whilst inside the prison system. This then results in further criminal activity when they are released.

Despite making a number of recommendations, the inquiry ultimately found that it was the responsibility of the state governments, not the federal government, to combat this issue.

The ‘Revolving Door’

Researcher from the Centre of Health Services at the University of WA, Craig Cumming, provided evidence to the inquiry of the ‘revolving door’ effect that is created through the current system in place.

“People attributed their incarceration to using meth. Sometimes that is because they have committed the property crime to fund their habit or they have dealt in drugs because it is the only way they can afford to take them. At other times they have committed a violent offence or an offence against a person because of the state they were in due to being intoxicated. Many prisoners then use meth as a form of self-medication.”

As stated by Cumming, many prisoners continue their use of meth inside the prison. This continues their addiction and they often end up back in jail having commit drug related crimes after their release.

In addition to this, most states and territories have laws in place that make drug use and possession a criminal offence with up to two years imprisonment. As a result of this many people find themselves in prison simply for using meth, without committing any additional crimes.

Due to the abundant availability of meth on the street, and the inadequacies of the current social services implemented to tackle this issue, meth addicts often end up in the criminal justice system. This is evidenced in the following graph which contains statistical data from BOSCAR indicating that levels in possession/use crimes have been increasing.

Problems On the Inside

During the inquiry, the Penington Institute argued that the idea that prisons are drug-free spaces is a myth and must be rejected in order to have a mature conversation around the issue.

“Our prisons are still chock-a-block with people with drug addiction problems. In fact, there is an ice problem inside our prisons as well; people are not only being incarcerated with drug addiction but continuing their drug addiction whilst inside.”

The evidence revealed that prisoners are more likely to enter the prison with an existing illicit drug problem and that their drug use may become more problematic whilst detained in a prison. This is a particular concern for those with meth addictions, because the availability and use of meth in prison is common.

Whilst it is known that prisoners use meth in prisons, the inquiry heard that there are inadequate treatment options available to them. Mr Cumming emphasised the importance of establishing treatment services in the prison system because the prison population is a group that is known to be affected by addiction to meth the most.

First Nations People

Solicitor at the Aboriginal Legal Services Wollongong, Caitlin Goodwen, believes that indigenous Australians have suffered from this lack of treatment options provided by the NSW prison system.

“Many of my clients are in jail as a result of their meth addiction and are able to continue using whilst inside. This then results in further criminal activity after they are released.”

Caitlin also strongly advocated for the use of alternate methods of dealing with this issue instead of through the criminal justice system. These ideas were echoed by the inquiry where evidence of the efficiency of these methods, in relation to the indigenous population, was revealed. The following graph shows the money that is saved per individual who undertakes alternate treatment methods.

What can be Done?

It was reported that the most effective treatment programs available in prisons are based on therapeutic community models. These methods have been demonstrated to reduce risk of the individual returning to prison after they are released by 50%. It involves a rehabilitation process that seeks to reconnect them with their community. The inquiry concluded that these programs could be improved by offering enhanced transitional services, such as pre-release and post-release programs.

Pharmacotherapy can also be an effective method of drug rehabilitation. This involves the replacement of the illicit drug with a legally prescribed substitute. Although pharmacotherapy is available for people with opioid addiction, there is currently no pharmacotherapy substitute for people with meth addiction. This means treatment options are restricted to behavioural therapies or drug detoxification programs.

Professor Rebecca McKetin is one of Australia’s leading experts in meth treatment and is currently trialling two new medications for meth dependence. Due to the availability of these two drugs on the market, Professor McKetin believes that the use and production of these drugs would be a cost-effective solution to treat amphetamine addiction if shown to be effective. Professor McKetin advised the inquiry that there is a role for both this form of therapy and psychological interventions.

Overall, the evidence presented in this inquiry indicated a lack of understanding about illicit drug use in Australian prisons. Whilst acknowledging that self-reported data often under-reports drug use, it is vital that accurate and comprehensive data is provided by all states and territories so that governments and drug treatment service providers have sufficient information to develop treatment programs for Australian prisoners.

What is Being Done?

In light of this lack of accurate data, the inquiry recommended that the Australian government, in partnership with the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, establish nationally consistent datasets and regular reporting of illicit drug use in Australian correctional facilities.

The Inquiry found that it was not appropriate that people were leaving prison with more problematic drug use patterns or with a related health issue due their drug use, as a result of their imprisonment. For this reason the Inquiry supports the use of treatment programs aimed at prison inmates during, prior to and after their release. The Inquiry also makes the recommendation for State governments to increase the focus on evidence-based approaches to treatment services in prisons.

However, despite the Inquiry voicing their support of these treatment programs being offered in prisons, they ultimately found that it is outside the Commonwealth government’s jurisdiction and is a service that is offered and funded by state and territory governments. Due to this, these programs are unlikely to be utilised through the NSW prison systems and two thirds of the prison population will continue to be affected by meth.