More research and understanding is needed to determine why Indigenous young Australians are reluctant to access education, a TAFE NSW educator has claimed.

The release of 2022 data has seen Indigenous education goals improving since 2020 but more needs to be done to understand Aboriginal history in relation to reasons behind the education gap.

Indigenous educator at TAFE, Belinda Craig, said that improving the gaps in education are complex, requiring a thorough understanding of Aboriginal culture, and how it relates to why accessing education for some Indigenous Australians is not a consideration.

“Most people don’t realise how recent Aboriginal children were stolen and can’t understand how that can still be affecting Aboriginal People and their families,” Miss Craig said.

“Most people are shocked to realise that there are Aboriginal communities in Australia that don’t have access to clean, drinkable water or that the prices of food items in communities are exorbitant.

“Health and living conditions in some Aboriginal communities are that of third world countries.”

In 2020, collaborative efforts between the Australian governments and representatives from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Coalition of Peaks led to the development of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap.

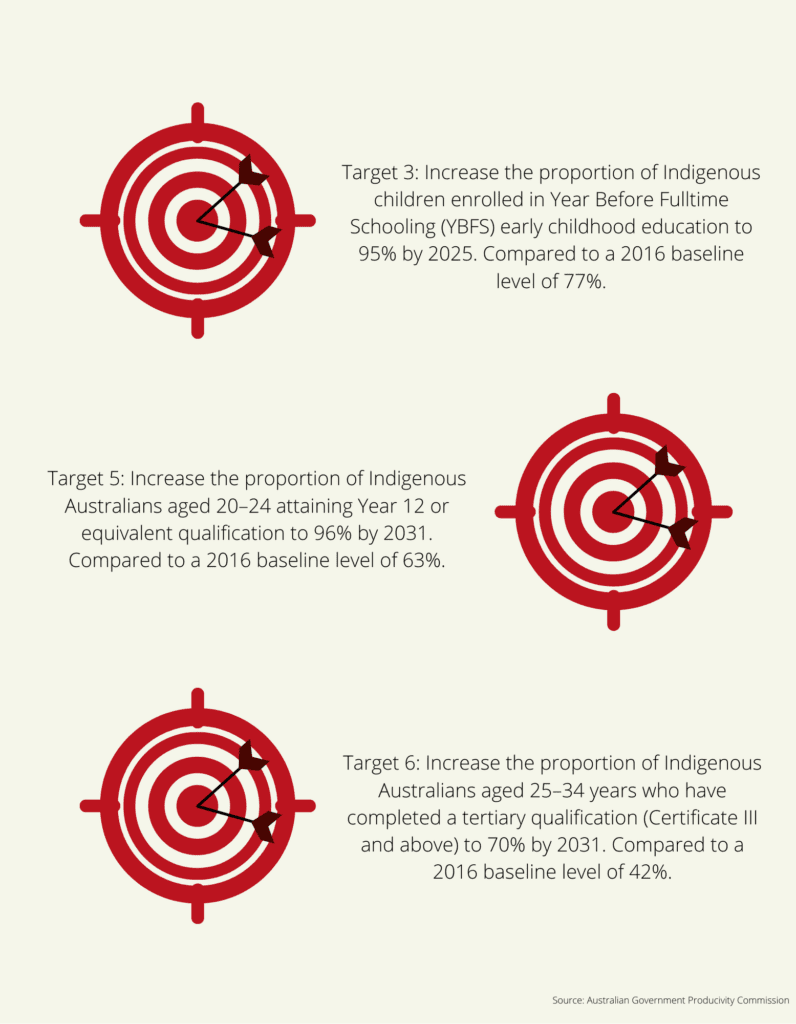

The Federal Government, through the initiative of Closing the Gap, identified Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples completing early childhood education, Year 12 or tertiary and post school education as areas needing significant improvement.

This agreement focused on four reform priorities, including 16 socioeconomic targets aimed at addressing current disparities. Within these targets, education and school readiness were highlighted as a matter of urgency.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare said Indigenous Australians with high levels of education have been associated with improved employment, wellbeing, health literacy, greater working conditions, income and various other social benefits.

Director and educator at Evolve Communities, Aunty Munya, stated that improving the education of Indigenous Australians is a complex issue.

“We feel that better education and understanding of the First Nations people and culture will help close the gap,” she said.

According to the ABS, data collected in 2015 indicated 43 per cent of individuals aged 20 years and over were taught about Aboriginal culture in school.

The Government, through Closing the Gap, has developed programs and policies such as Connected Beginnings with 15 funded initiatives that aims to enhance the integration of early childhood health, education and family support services.

According to data from the Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision in 2019, the enrolment rate of Indigenous children in early childhood education during the year before full-time schooling is 92 per cent.

The 2022 annual data compilation report has stated the enrolment rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in early childhood education experienced a notable rise, reaching a total of 96.7 per cent.

The increase marks a significant improvement compared to 2016, the baseline year, where the enrolment rate was 76.7 per cent.

This achievement reflects significant progress towards meeting the enrolment rate of 95 per cent the national target by 2025.

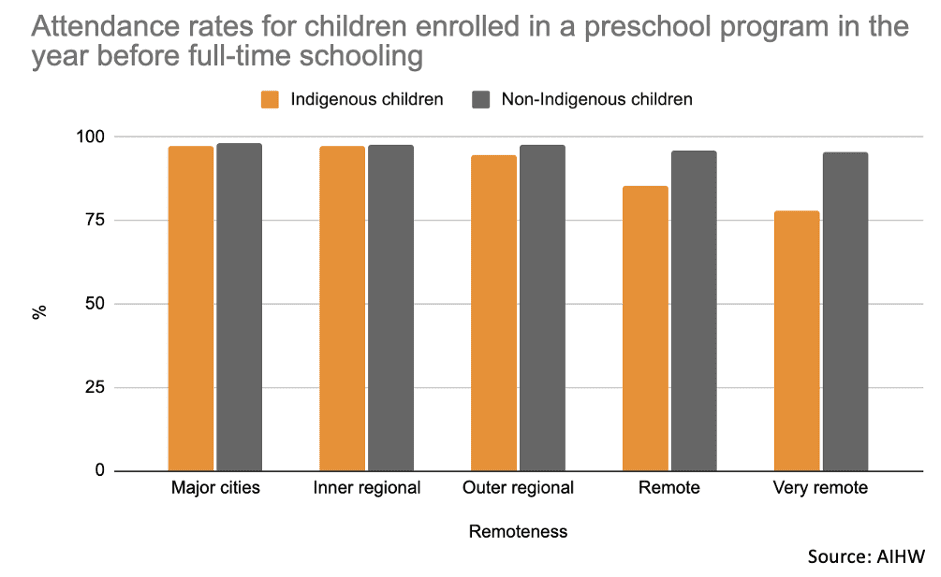

However, attendance rates for Indigenous children living in remote or very remote areas was less than those of non-Indigenous children.

In 2019, the Australian Early Development Census stated in very remote areas, Indigenous children had a 1.8 times higher likelihood of being deemed developmentally vulnerable in one or more domains including language and cognitive skills compared to their counterparts residing in major cities.

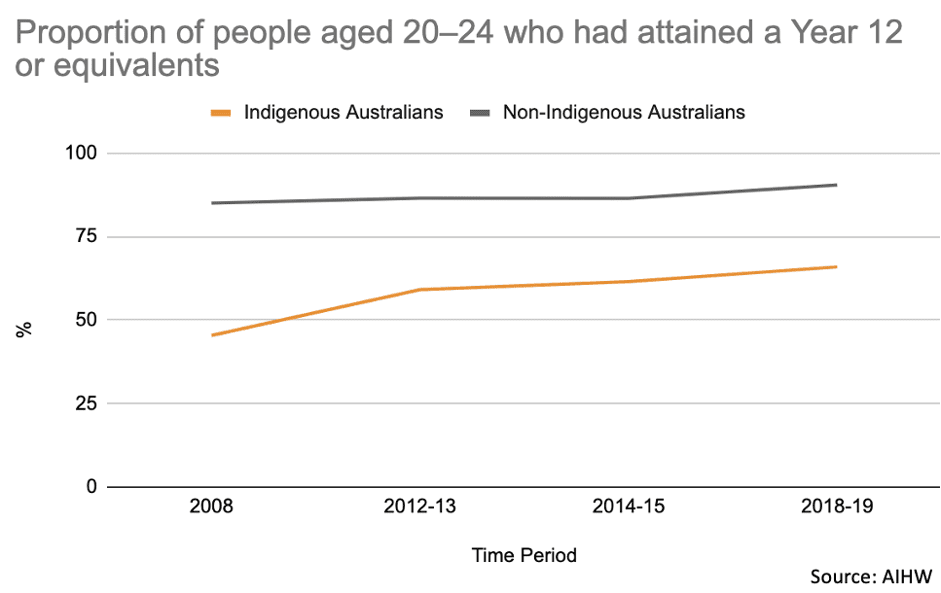

Between 2008-09 and 2018-19, there was an 11 per cent increase in the proportion of individuals aged 20 years and above who completed year 12. Simultaneously, there was a decrease of the same magnitude in the proportion of individuals completing year nine or below.

Indigenous Australians achieving year 12 certificates or equivalent, including certificate II or above had a 21 per cent increase over the 11-year period.

The National Indigenous Agency stated the Wuyagiba Bush Hub is an initiative that helps young people in remote areas to access higher education. The hub offers a program that combines cultural learning with academic skills. In 2019, nine students completed the program, with five being accepted to Macquarie University and four to the Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education.

In a media release, Commissioner Romlie Mokak, said that, despite the encouraging statistics, it’s too early to determine whether the Agreement will be a success.

“It is still early days, but monitoring under this Agreement will look to show whether the actions have occurred, and if the life outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have improved,” he said.

Alongside location, various aspects contribute to the gap in education between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, particularly that of inter-governmental trauma which has developed into a mistrust of the school system.

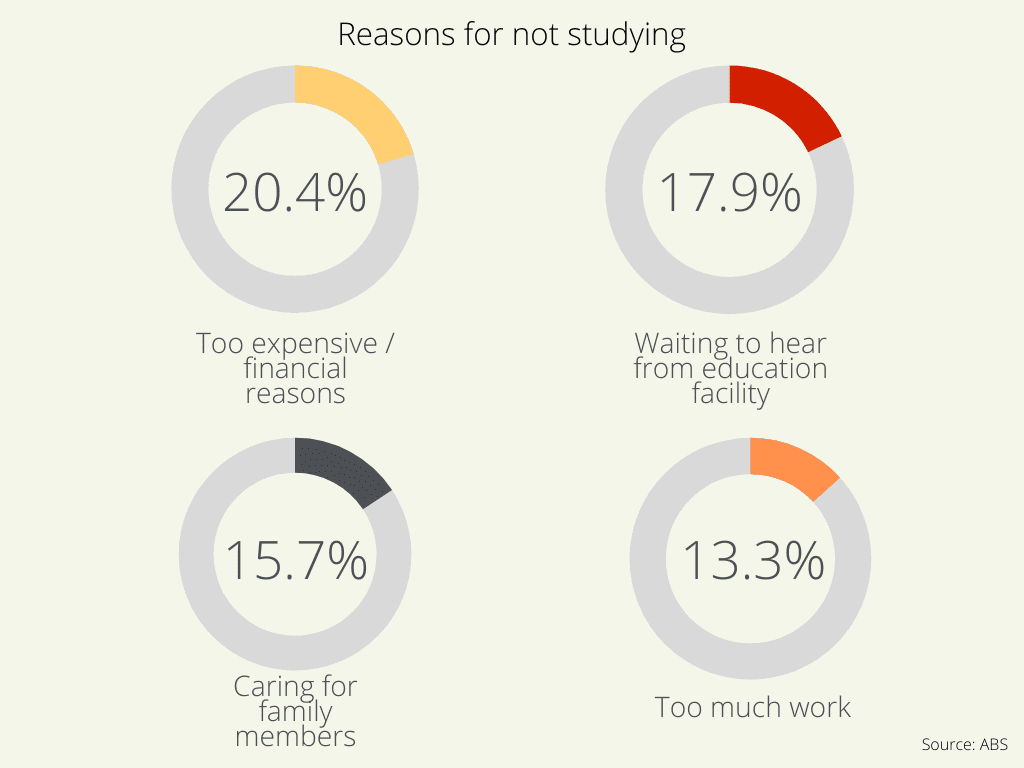

“Family views on the need for education impact the attendance and familiar responsibilities such as caring for siblings and vulnerable family members which can be considered to be of higher importance,” Miss Craig said.

According to data published by the ABS, financial constraints are the primary hurdle faced by Indigenous individuals seeking to pursue further education or acquire additional qualifications.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare emphasised the importance of adult learning and its impact upon social outcomes for people in more disadvantaged groups.

Those who participate in post-school learning experience positive changes in their behaviours, such as increased physical exercise, decreased alcohol consumption and smoking, as well as enhanced social and emotional wellbeing.

In 2022, approximately 47 per cent of individuals belonging to the Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander community had successfully achieved tertiary qualifications at a national level, an increase from 42.3 per cent in 2016.