When asked where he’s from, Om Dhungel never says Bhutan — his answer will always be Blacktown, the Western Sydney city. As a refugee, he knows the importance of a community. “If I say I am from Bhutan, I will only be a part of the small Bhutanese community. But if I say I am from Blacktown, I will be a member of the whole community,” Dhungel said, after wrapping up A Literacy Lunch at the Wollongong City Library.

Dhungel was 30 years old when he fled Bhutan with his wife to escape Bhutan’s ethnic cleansing. With a population of 84 per cent Buddhists, Bhutan sees those of Nepalese ancestry that practise Hinduism as a political threat. As a result, more than 100,000 Bhutanese citizens of Nepalese descent were forced out of the country during the 1990s.

For the next decade, refugees resided in seven distinct refugee camps scattered across Nepal. In 2007, the third-country resettlement program commenced, leading to the majority of the refugees being relocated to various countries, including Australia.

In 1998 Dhungel arrived in Australia on a student visa to study a Master of Business Administration at the University of Technology Sydney. He was later granted a refugee visa and obtained an Australian citizenship on April 28, 2004.

Dhungel was born a citizen of Bhutan, passed the days as a refugee, and now lives as a citizen of Australia. But what does it mean to be a citizen of any country to Om Dhungel? He defines it as belonging.

“I so much wanted to belong somewhere, and the Australian citizenship gave me that sense of belonging,” he said.

Recalling the days of the ethnic cleansing, Dhungel recounts how King Jigme Singye Wangchuck played the double game. On one side he was beating Lhotshampas (southern Bhutanese people) to death, and on the other side, he was calling for the Lhotshampas in his residence to celebrate festivals and spread the word of how much he values them.

Dhungel was one of the Lhotshampas who was invited to the palace, but once he recognised the King’s tactics, he made excuses to run away from it.

As a government employee, Dhungel was guaranteed to constantly be under close watch from security. However, after receiving confidential information from his friends that he was to be arrested, Dhungel had to make the difficult decision to leave Bhutan.

Leaving behind his two-year-old daughter and his wife, Dhungel was unsure he’d ever see them again. Despite losing everything, Dhungel realised he still kept the capacity to love and care for others — something he’d been doing his whole life.

“I lost my possessions, my salary, my status, my career, my country. And in that fall, I gained everything,” he said.

To cross the border, he had to lie to the security guards, claiming he was going to India for vehicle maintenance. Once he crossed, he waited 48 hours for his family to follow.

“[It was] the longest 48 hours of my life,” he said.

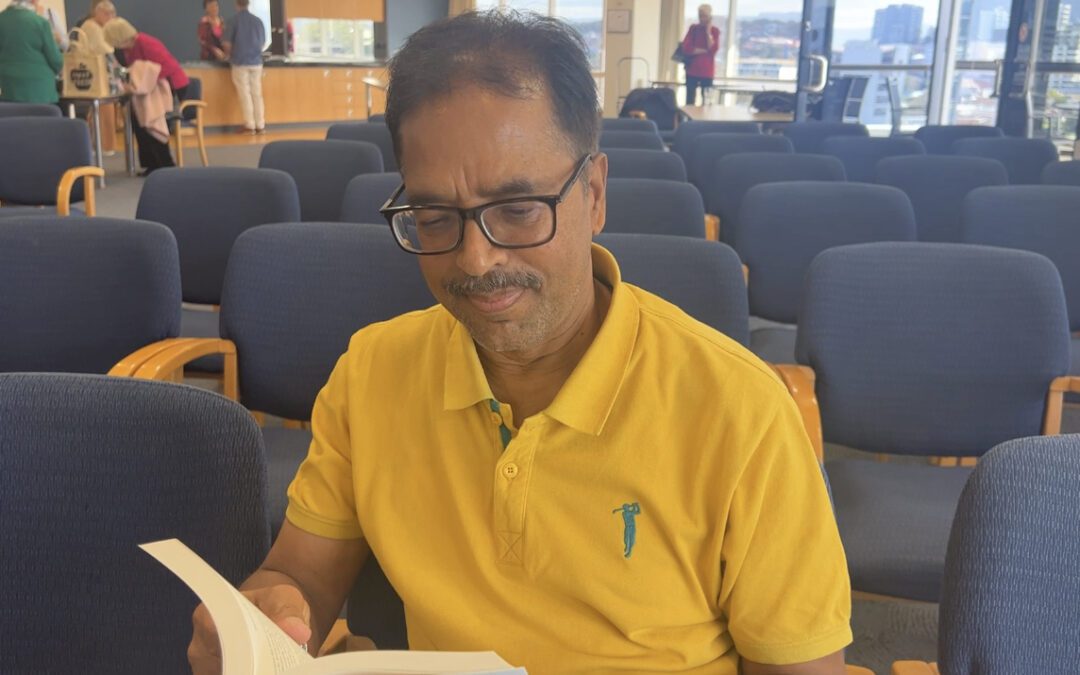

At A Literacy Lunch, Dhungel arrived early and began setting up the stage. The library hall was packed and ready to listen to Dhungel’s journey. He started, posing the simple question, “What comes to mind when you hear Bhutan?”

Responses ranged from “Himalayas”, to quips about the culture, to finally one woman in the last row exclaiming it was the “happiest country in the world”. Dhungel wasn’t shocked, he knew that many people were unaware of Bhutan’s dark history. He explains this was the reasoning behind publishing his book.

“The country which you see endorsing happiness over economy is the same country that overnight turned its own citizens into refugees and created one of the biggest refugees in the world,” he said.

Silence was the only response from the audience as Dhungel told his story. People sat, shell-shocked, as Dhungel explained how the Bhutan military raped Lhotsamphas women, arrest young boys without reason and beat people severely during the period of cleansing. Dhungel related this to Blacktown, often called Sydney’s most dangerous suburb.

“Blacktown is so rich in cultures and traditions, its population is growing each day. I have been living there for more than two decades, and I walk at night, nothing has happened,” Dhungel said.

“People don’t know about this side of Blacktown, they just focus on the negative parts. Similarly in Bhutan, many are unaware of its tragic past, everyone is in awe of their happiness policy.”

To this day Bhutan doesn’t accept Lhotshampas as Bhutanese, instead referring to them as “illegal immigrants”. However, Lhotshampas have been in Bhutan before the Bhutanese monarchy even existed. Dhungel explains that as much as belonging, having citizenship also means having an identity.

After completing his Master of Business Administration at UTS, Dhungel worked at Telstra for 10 years before he decided to dedicate himself to community building amongst the Bhutanese and Blacktown population.

In 2007, Dhungel, with the help of his family and friends, established the Association of Bhutanese in Australia.

The organisation successfully resettled more than 5,000 Bhutanese refugees in Australia, and as a result, earned recognition as one of the most accomplished refugee settlement initiatives in Australia.

During this time Dhungel also started writing a book on his experience. Upon completion he decided to reach out to Anthony Albanese to write the foreword. Before adopting the position of Prime Minister of Australia, Albanese was the Local Member of Parliament for Grayndler, covering most of Sydney’s Inner West — Dhungel’s community.

After three long months, Dhungel finally received a response from the Prime Minister. Albanese congratulated him on his efforts and reminisced about their past conversations about Bhutanese refugees.

Dhungel was struck by Albanese’s description of his book and decided to feature them on the cover.

“What you hold in your hand is a great Australian story.”

Om Dhungel is the author of Bhutan to Blacktown: Losing Everything and Finding Australia.