It was hot at Mary River, just east of Darwin. The sun was burning down mercilessly on researcher Kerrylee Rogers and her team. They had covered up almost every inch of their skin, not only to avoid sunburn but also to escape the mosquitos that kept swirling around them in a frenzied attack. They took their steps carefully, making sure that no crocodiles were hiding just beneath the surface of the water.

“It’s hard working up there,” University of Wollongong research Professor Kerrylee Rogers says,

“If there’s crocodiles, you’re going nowhere near the water.

“If you want to work in the mangrove forest, you do it when the tide’s out.”

Prof. Rogers is a member of the Environmental Futures Research Centre at UOW. Her research focuses on coastal and aquatic ecosystem vulnerability to climate change, adaptations to climate change, and opportunities for mitigating climate change through improving restoration, conservation, and management of coastal and marine ecosystems. The true potential of these ecosystems and role in mitigating climate change lies beneath the water’s surface and it is called blue carbon.

“When we talk about blue carbon, we’re talking about the carbon that’s contributing to climate mitigation,” she says.

“It’s about the capacity of coastal marine ecosystems to pull carbon from the atmosphere and store it.”

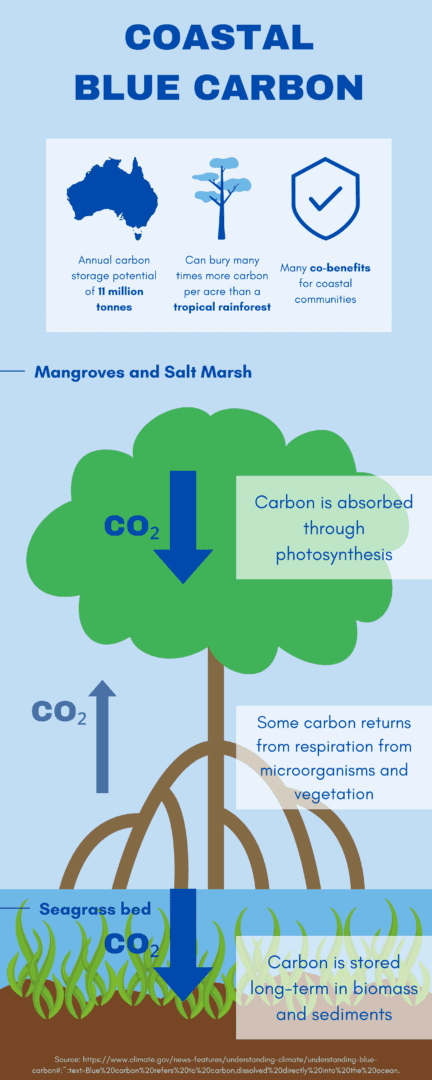

The blue carbon cycle begins with the storage of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by marine and coastal ecosystems. Plants like mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes use photosynthesis to take in CO2 and convert it into organic matter through a process of carbon sequestration. These ecosystems store carbon in various forms, from living plant matter to the sediments beneath the water or soil. This storage can persist for centuries or even millennia, making them reliable long-term carbon sinks. It is estimated that Australia has an annual carbon storage potential of 11 million tonnes.

The blue carbon cycle begins with the storage of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by marine and coastal ecosystems. Plants like mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes use photosynthesis to take in CO2 and convert it into organic matter through a process of carbon sequestration. These ecosystems store carbon in various forms, from living plant matter to the sediments beneath the water or soil. This storage can persist for centuries or even millennia, making them reliable long-term carbon sinks. It is estimated that Australia has an annual carbon storage potential of 11 million tonnes.

“If you look at Australia, our tropical areas are in the top end. It’s very hot, humid, monsoonal,” Prof. Rogers says.

“If we have sea level rise, mangrove forests are going to encroach a bit more land. Now, the unique part across the top of Australia is that it’s not developed.

“So that capacity for the mangrove forests to adapt quite freely and move across coastal floodplains is a lot more evident, particularly across the top of Australia. More than anywhere else in the world.”

When it comes to mitigating climate change, mangrove forests and salt marshes play a crucial role. Environmental researchers worldwide are looking for ways to increase the carbon storage of these ecosystems. Prof. Rogers research revolves around gathering data: Finding more information about specific coastal wetlands, examining their current state and developing solutions to restore, conserve, and manage them.

“If you reinstate tides, it actually allows sediment to come in,” she says.

“The sediment creates more space for storage of carbon vertically.

“That’s where a lot of restoration activities are focusing on: Increasing that vertical space so you have more capacity to store carbon below ground in particular, but also to share it with other ecosystems nearby.”

Apart from storing carbon, coastal wetlands provide many more services to coastal communities that make them worth protecting. Prof. Rogers has seen the positive impacts these ecosystems can have while working in Brazil and Vietnam, countries where people live amongst mangrove forests. There local communities have understood that the mangroves support their fisheries and provide economic stability. Preserving these habitats does not only combat climate change, but also promotes sustainable development.

“The people in those countries are very connected to mangrove forests,” she says.

“They get timber from it. They fish from it. It protects their shorelines.”

An important part of Prof. Rogers job is leaving the safe confines of her office and experiencing the environment and current state of coastal wetlands firsthand. She does field research in mangrove forests and salt marshes that stretch across northern Australia, often spending several weeks out in the bush. It is a unique and exciting job, even if the circumstances can be challenging.

“My lunch is always tuna fish because it’s a bit of protein,” she says, with a laugh.

“And wraps, because wraps don’t squash in your bag.”

But to Prof. Rogers seeing the beauty of Australia’s wildlife makes it all worth it. Even when she attends a conference, she always signs up for the field trip days. And then, when she has to decide if she wants to go to the gin distillery, the chocolate factory, or the wetland, the answer is clear to her: The wetland it is. Having always been an outdoorsy person, she is most excited that she gets to see places that no tourists can get to when conducting her research.

“I get to see some amazing places that most people don’t get to see,” she says.

“You got stingrays and sharks and everything. It’s amazing.

“You don’t get to do that. I get to do that though, so that’s pretty cool.”

However, the preparation for these expeditions starts long before she even thinks about stepping on a plane and flying to the other side of Australia. And even longer before she analyses all the gathered data and can draw conclusions from her discoveries. It is a complex and tedious process that does not only include shipping vast amounts of equipment across the country but also engaging in dialogue with local indigenous communities.

“To work up there, we’ve got to apply for scientific permits and that can happen 69 months in advance,” she said.

“When planning our trip, we’re looking at the tides and the season and there’s a lot of logistics that go into that originally.”

When Prof. Rogers is not out doing field research, she can be found in a classroom at the University of Wollongong conducting lectures on coastal management and processes. She has a long history with the university, considering that years ago, she was an undergraduate student in Environmental Sciences herself. To her, it comes as no surprise that she ended up in this field. She always liked exploring the world around her, walking through the forest and bush-crafting. However, it was a professor that piqued her interest in coastal wetlands.

When Prof. Rogers is not out doing field research, she can be found in a classroom at the University of Wollongong conducting lectures on coastal management and processes. She has a long history with the university, considering that years ago, she was an undergraduate student in Environmental Sciences herself. To her, it comes as no surprise that she ended up in this field. She always liked exploring the world around her, walking through the forest and bush-crafting. However, it was a professor that piqued her interest in coastal wetlands.

“It was Professor Colin Woodroffe,” she says.

“I remember doing an assignment on mangroves and being so intrigued by them.

“It just really inspired me.”

Today, many years later, the roles are reversed: She is no longer sitting in front of her professor and listening to a lecture. It is her now, standing in front of a class, who is pointing at a whiteboard and explaining a new theory to students. In her lectures, she tries to ignite that spark within her students that Prof. Woodroffe once ignited within her.

“Kerrylee’s own passion for coastal management and processes is infectious,” UOW student Oceane Roumeas says about her lectures.

“She genuinely cares about the subject and her enthusiasm is evident in the way she teaches.

“Her excitement is motivating and inspiring for students.”

When Prof. Rogers is asked why people should learn about coastal wetlands her answer reveals her down-to-earth attitude. But much more, it shows her passion and respect for the environment.

“I’m not sure everyone needs to know the potential of coastal wetlands,” she says.

“I think everyone needs to have a clearer understanding of ecosystem services more generally and start to value all ecosystems.

“The thing that I would like people to get is that sort of appreciation of what nature does for us, and it’s a huge amount of things.”