Innovation within limits

Visual communicators work at the intersection of creativity and intellectual property; and operate in a complex realm of copyright laws. They rely on these laws to protect artistic creations, but the laws also restrict creativity. So, can other artist’s work be used as inspiration. In the copyright case of Pokémon vs Redbubble media practitioners can gain insights into the application and outcomes of copyright law.

Copyright – Understanding the basics

In Australia, we are governed by the Copyright Act 1968, enacted to protect creators’ original work, ensure they have control over their work, and determine how others can use it. In “The Journalist’s Guide to Media Law“, Pearson & Polden states that “copyright laws protect the expression of the creative output rather than the idea”. The inherent authorship and ownership of a piece begins upon creation. Copyright protects original ideas and incentivises the innovation of new ideas; in saying this, there is debate of what is new in a remixed world.

The battle: Pokémon vs. Redbubble

In 2017, The Pokémon Company (TPC) enforced its intellectual property rights, alleging that the Australian company Redbubble Ltd, an online market, had allowed its users to upload and sell copyrighted designs that belonged to TPC.

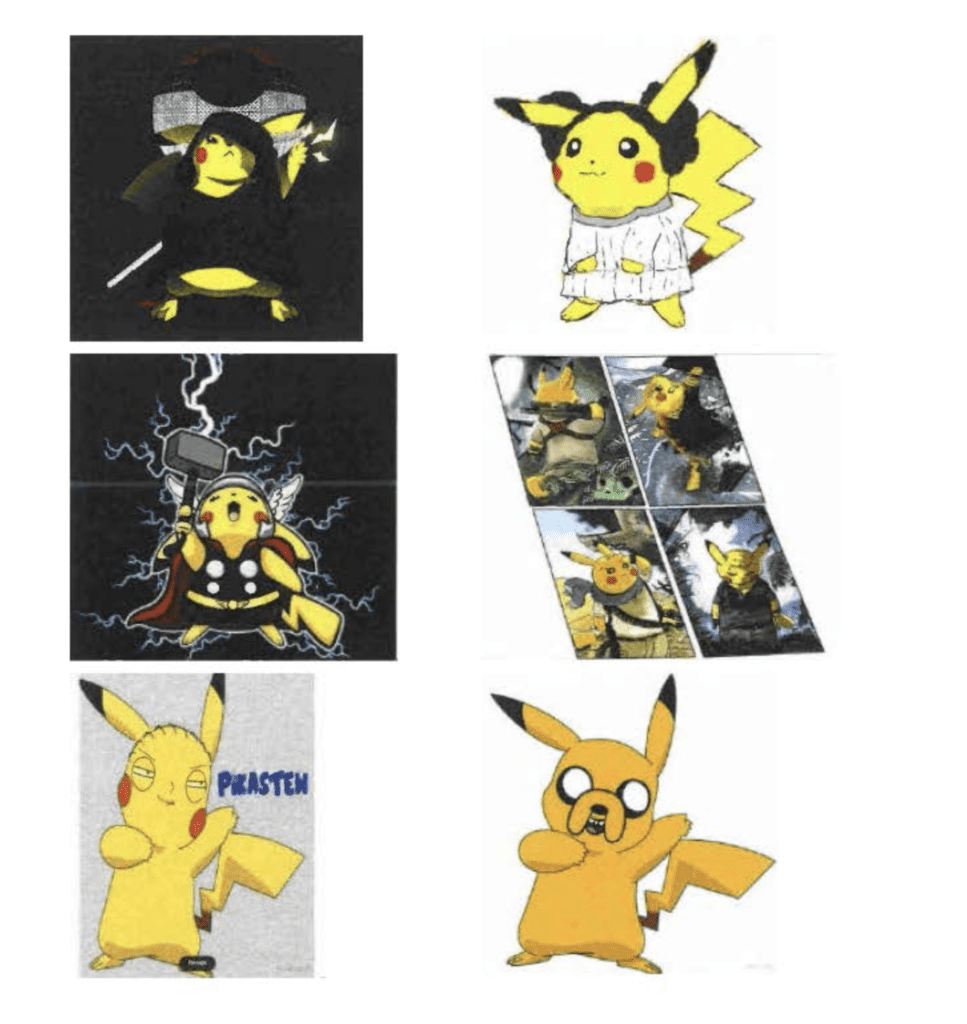

There were several designs that TPC claimed had infringed on their rights; some of these images were created using a technique called “mashup designs,” a transformative process of combining features of multiple characters.

TPC contended that Redbubble marketed these images with misleading advertisements, as users searching for Pokémon products were directed to Redbubble, and it was unclear on their website that they had no affiliation to TPC. In addition, Redbubble pricing for these products were also within range of official products offered by TPC.

TPC felt their intellectual property was being exploited commercially, rather than just a case of artistic interpretation. The judge and jury concluded that Redbubble infringed upon Pokémon’s intellectual property rights. Still, TPC could not show evidence of significant financial loss, resulting in Redbubble only paying them $1 in damages and covering 70% of the legal fees incurred during the dispute.

The designs were transformative, so what was the issue?

Redbubble argued that its designs fell under fair dealing, with the claims that they were produced for parody or satire. Judge Pagone acknowledged that some designs were comical. However, Redbubble could not prove that the designs were created with the intention of parody or satire. There was also no added commentary or criticism about the original work. Ultimately, the designs were transformative, using elements from the original work without changing or adding meaning, commentary, or criticism.

Learning from other cases

In a similar copyright case, Dr Seuss Enterprises sued ComicMix for a book called “Oh, the Places You’ll Boldly Go!” which combined elements of Dr Seuss’s “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!” with characters and themes from Star Trek.

ComixMix claimed to have transformative use because they had added “extensive new content,” But this was not enough to meet transformative work, as it did not add new expression, meaning or message that altered the original work. So ComicMix failed to argue fair dealing as a defence.

Similarly, Dr Seuss Enterprises vs. Penguin Books legal case centred on the book titled “The Cat NOT in the Hat!”, which was a parody of Dr Seuss’s children’s book “The Cat in the Hat” Dr Seuss brand filed a lawsuit alleging copyright infringement against Penguin Books, for publishing this book without seeking permission from them.

The book was said to be created for humour and satire, but it did not comment or criticise the original and thus doesn’t fall under fair use. During this case, the court highlighted the distinction between parody, where copyrighted work is used as the primary focus, and satire, where the copyrighted work acts as a vehicle to comment on another subject.

Parody relies on mimicking the original work to convey a message; thus, using the likeness enhances the message. In contrast, satire can exist without this and would need a rationale for using the original copyrighted material. Justice Kennedy commented, “The parody must target the original, and not just its general style, the genre of art to which it belongs or society as a whole.”

What is parody or satire?

In Australia, the concept of parody or satire is one of the purposes for which fair dealing with copyrighted material may be allowed under copyright law. Parody or satire is a transformative expression using others’ work, often for commentary, criticism, or humour.

In a parody, elements from the original work are used to enhance the effect, while satire is a broader commentary that uses humour, irony, or sarcasm to criticise; satire doesn’t require using specific elements from original works to make its point.

Is there a difference between Fair use and Fair dealing?

Both fair dealing and fair use are legislations that provide exceptions to copyright infringement, but they operate differently.

Fair use under the United States law is more flexible than Australia’s fair dealing exemptions, with the courts determining whether the use of work is fair by looking at four factors.

- The purpose, whether it was made for commercial reasons or non-profit educational purposes.

- The nature of the copyrighted work.

- The amount and portion used in relation to the copyrighted work.

- How it affects the value of the copyrighted work.

The four factors are the same for fair dealing and fair use, but with fair use, the list is more like an example, and there can be many more instances where you can fairly use materials without permission.

With fair dealing, there is no general exception for using copyrighted works. To be considered fair dealing, it must be used for one of the following categories:

But these exceptions have limitations, like the amount of work being used; when criticising or reviewing, you must acknowledge the original author and title, and the dealing must be fair.

Fair dealing and fair use differ significantly in terms of their interpretation. Fair dealing is limited to specific uses explicitly outlined in the law, being more restrictive and can only be applied for predefined purposes. Fair use offers a more subjective list, where using fairness criteria can be determined as fair use, even if it’s not explicitly stated.

What does it mean?

When using copyright materials, consider why you are using them, how you are using them and for what purpose. We should be mindful when using others’ work under the banner of creative freedom that we do so without harming their values. When using work for parody or satire, we should create transformative work that makes comments or criticism of the original work. As visual communicators and media practitioners, we observe the current and historical legal cases to gain valuable insight into how to operate within the legal frameworks, as the legal system is constantly evolving.

There are distinctions and considerations to know about fair dealing and fair use when using others’ work without permission. In most cases, communicators argue that their work fits under parody or satire, but these can be subtle and subjective. These cases emphasise the importance of carefully considering and understanding the copyright laws as visual communicators and media practitioners.

Navigating this complex environment successfully, creators and designers should ensure that their work adds meaningful commentary or new expression to the original work rather than merely replicating it. And to be aware of the differences in legislation between countries.