Global lockdowns, store closures and rising unemployment amid the COVID-19 pandemic are causing consumer retail spending to decline and wreaking havoc on the fashion industry and garment supply chains.

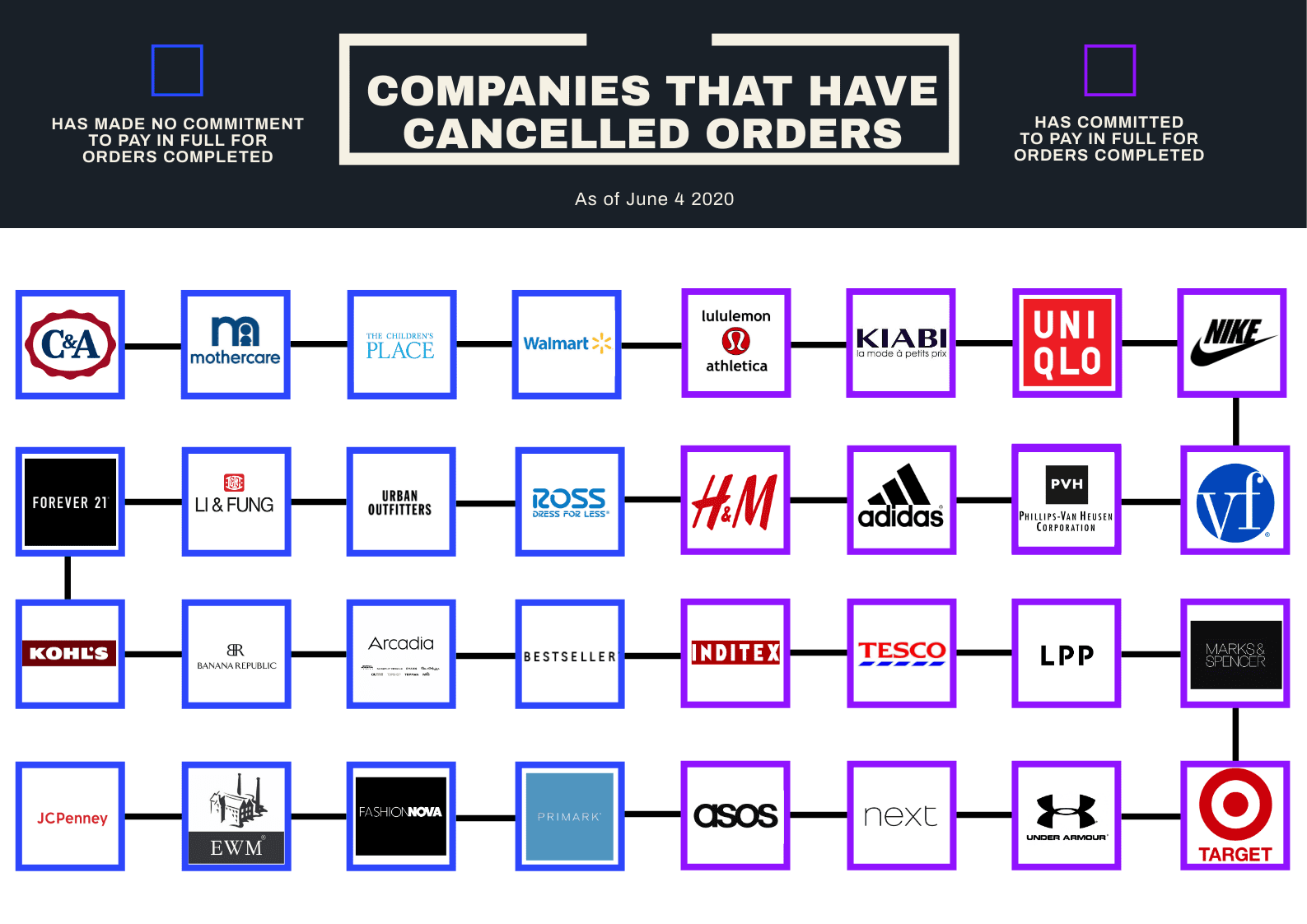

Major clothing companies including Topshop, Urban Outfitters and Forever 21 have cancelled and postponed orders made before COVID-19 which has led to stockpiles in factories of completed and in-production garments.

To reduce the economic impact of declining retail sales, many companies have refused to pay their suppliers for orders. Millions of garment workers have had their salaries cut and thousands of factories are permanently closed as a result.

While countries including Australia, the United States, and Europe were in lockdown, the garment industry in Bangladesh suffered a $3.5 billion loss since the arrival of COVID-19.

As the second-largest apparel producer after China, this figure is expected to reach $6 billion this financial year.

The textiles and garment industry accounts for 84 per cent of Bangladesh’s exports and without orders from western clothing brands, a functioning economy and the welfare of its population are at risk.

Data Source: Center for Global Workers’ Rights (CGWR) April 2020.

CARE Press and Media Coordinator Ninja Taprogge said the coronavirus crisis had exposed the fragility of the garment industry.

“Suppliers and governments have been starved of the resources to meet their obligations to the workers, who are now bearing the brunt of the impact of the crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic has broken the supply chain and laid bare the reality behind claims of its ‘resilience’ and ‘sustainability’,” he said.

In the supply chain, the materials and fabric are paid upfront by the factory owners. When the owner and their employees get paid depends on when and if the buyer pays the invoice, which is raised once the items are shipped.

Now, with months’ worth of clothes not shipped, the suppliers are out of pocket for money already spent on materials and are unable to pay for the operation of the factories including the owed wage of its workers.

Worker Rights Consortium Program Coordinator Vincent DeLaurentis said without decisive action taken by brands, national governments, and international groups, poverty in Bangladesh will only get worse.

“Workers in Bangladesh were already living paycheck to paycheck, with the majority having no savings and were often supporting family members in rural communities,” he said.

“The interruption of production and non-payment of wages caused by COVID-19 undermined the precarious position workers were in and left them unable to support themselves.”

The situation has provoked public outcry with social media users calling for companies to be made accountable and forced to pay for what they ordered. The #PayUp social media campaign and petition, in particular, has pressured companies to take responsibility.

.@GapInc .@Kohls .@Topshop .@Peacocks demanding discounts, refusing to #PayUp, while factories struggle and the women who make our clothes become increasingly housing and food insecure. More in .@Forbes: https://t.co/dORXFBQdm3 pic.twitter.com/eG3b07HurB

— Ayesha Barenblat (@abarenblat) May 11, 2020

According to data from the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), by April 2020, approximately three out of four million workers in Bangladesh were experiencing the financial burden from factory closures and unpaid wages.

In an industry already scrutinised for poverty-line wages, without savings to fall back on, many workers are unable to afford health care and they now face destitution and starvation, putting them at higher risk of contracting the coronavirus.

“This situation of social disempowerment combined with COVID-19 can lead to a prolonged livelihood crisis and severe marginalisation which could also increase the number of people requiring safety nets,” Taprogge said.

The undue state of the garment supply chain is what major clothing companies profit from and continue to exploit.

The same brand may be purchasing from multiple factories around the world to take advantage of the different minimum wage.

In a practice called underground bidding brands will use quoted prices from one factory to negotiate a lower price at another factory. The fastest turnaround time for the lowest price receives the deal.

“Brands have a way of moving to chase after cheaper production and I am sure they will bounce back from COVID-19 regardless. However, they have a responsibility to the workers who have made them clothes and, therefore, profits for decades,” DeLaurentis said.

“Abandoning the workers now and refusing to pay for orders will set an awful precedent that leaves workers vulnerable to being discarded without concern.”

According to the 2019 report by Oxfam Australia, 100 per cent of garment workers in Bangladesh earn below the living wage when compared against Global Living Wage Coalition benchmarks.

Eighty-five per cent of workers reported they regularly run out of money at the end of each month and are unable to meet their basic needs.

For factories to offer companies cheaper production it is at the expense of the workers through low wages and poor factory conditions.

With trends released weekly as low-cost low-quality garments, consumers are buying and disposing of clothes more frequently.

This fast-fashion consumer behaviour is not only damaging to the environment, it is detrimental to the lives of the garment makers.

The anti-poverty charity War on Want said most workers are expected to sew 2000 garments during one shift and are punished if they don’t meet the expectation.

“As well as earning a pittance, Bangladeshi factory workers face appalling conditions. Many are forced to work 14-16 hours a day seven days a week, with some workers finishing at 3 am only to start again the same morning at 7.30 am,” the charity said.

“On top of this, workers face unsafe, cramped and hazardous conditions which often lead to work injuries and factory fires.”

The 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh was the tipping point to expose the dangers and risks within some factories and to action a plan to improve them.

The eight-story building collapse killed 1134 people and injured 2500. The Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh was established and more than 200 companies signed the Accord.

The legally binding agreement between global brands, retailers and trade unions significantly improved workplaces by funding improvements to buildings. This included implementing fire doors and structural work, regular safety inspections, safety training, informing workers of their rights, and providing a platform for workers to file complaints.

Feature image: In the foreground, Roksana Khatun, a sewing operator at the Viyellatex garment factory, Gazipura, Bangladesh, Nov. 2015. Credit: Ismael Ferdous/UNSGSA via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)