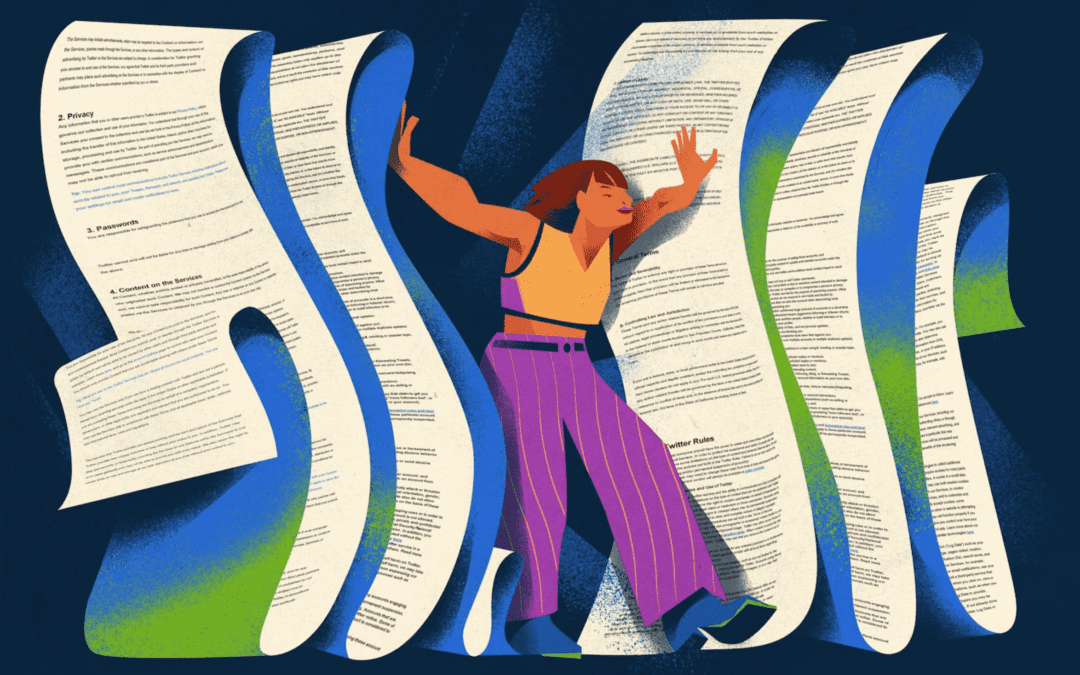

In the late 1990s, when Google was merely a search engine, its first privacy policy offered only 600 words to explain its collection and use of personal information. Over the past 20 years, that same privacy policy has been rewritten into an extensive 8,000-word explanation of the company’s data practices. This takes an average consumer over 30 minutes to read.

Okay, who are we kidding: no one has time for that.

In fact, 94% of Australians don’t. The average time spent by Australian users viewing the Google Privacy Policy was less than two minutes! (DPI 7.5.1)

So, when presented with a lengthy policy consumers mindlessly click “agree,” claiming we’ve read the data policy and agree to the terms and conditions. But, in the eyes of the law, we’ve given companies consent to use our personal data.

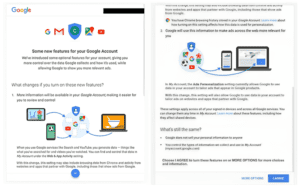

In 2020, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), launched legal proceedings against Google claiming they misled consumers regarding the expansion of its use and collection of personal data. A pop-up notification was released between June 2016 and December 2018 seeking account holder’s consent to use their personal data across Google Services to “make ads across the web more relevant for you”.

Google account holders were prompted to click “I agree” which meant that Google could begin collecting a wider range of personally identifiable information surrounding online activity. This included data from Google Services and third-party sites not owned by Google, via integrated marketing platform DoubleClick.

This resulted in millions of Australians providing ‘additional, valuable personal information to Google about their internet activity, which Google in turn used to increase the value of its advertising products for commercial gain’ (38C Concise Statement).

The ACCC alleged that Google designed the notification to maximise the number of account holders who checked ‘I agree’ rather than to maximise those who actually understood the implications of agreeing to the changes. Thus, the ACCC argued that as consumers could not have properly understood what changes were being made nor how their data was being used they did not – and could not – give informed consent.

“We believe that many consumers, if given an informed choice, may have refused Google permission to combine and use such a wide array of their personal information for Google’s own financial benefit.”

However, Google alleged that the notification was designed in consideration of some of its account holders being “Skippers, Skimmers and Readers” of privacy policies and therefore only provided the information necessary to understand the changes.

The court ultimately found that by users clicking ‘I agree’ they gave authority and explicit consent for Google to make the proposed changes and use their data.

Google’s privacy policy had previously stated that it would:

‘…not combine DoubleClick cookie information with personally identifiable information unless we have your opt-in consent.’

On June 28, 2016 Google deleted this statement and replaced it with:

‘…depending on your account settings, your activity on other sites and apps may be associated with your personal information in order to improve Google’s services and the ads delivered by Google.’

It is important to look at exactly what governs company’s rights to use personal data and what ‘consent’ really means. The main policies regarding privacy are the Australian Privacy Principles (APP). These are principles-based law which encourage companies to remain flexible in in their exercise of privacy policies. Throughout the APP’s ‘consent’ is mentioned multiple times as a means of collecting personal and sensitive information.

Most notable to the ACCC v Google case is Part 3 Section 7 of the APP. Subclause 7.1 states that:

If an organisation holds personal information about an individual, the organisation must not use or disclose the information for the purpose of direct marketing.

However, subclause 7.3 states that:

Despite subclause 7.1, an organisation may use or disclose personal information (other than sensitive information) about an individual for the purpose of direct marketing if:

b.i. the individual has consented to the use or disclosure of the information for that purpose;

Laws require consent but make no mention of meaningful consent.

There are no laws to protect users who meaninglessly consent and further, no statutory right to sue for a breach of privacy. The Privacy Act only offers to “provide a means for individuals to complain about an alleged interference with their privacy” (2A).

With little Australian law governing the acquisition of ‘meaningful’ consent, digital platforms are able to continue to collect valuable data from consumers and users.