Under the command of the Commonwealth, the Australian Infantry Force lost 39,652 sons and daughters in the Second World War. Frank Richard Archibald was one of them. A proud Gumbaynggirr man killed on the battlefields of Papua New Guinea on November 24th, 1942. His life, and his death sewed a new stitch into the fabric of Australia’s wartime history.

At the age of 25, Frank signed up his life on the dotted line of an Australian Imperial Forces enlistment form. He walked away from that recruitment stop in Kempsey, NSW, a man willing to die for a country that refused to acknowledge him as a citizen. Clean, brown leather boots laced and hat tilted clean across his right brow, Private Frank Richard Archibald set off to train in Greta, NSW, soon to join the 2/2nd Infantry Battalion.

After weeks of intense physical conditioning, with his brother Ronald and his uncle Frank Snr by his side, Frank set sail for the shores of Palestine and the doorstep of Europe. A patch of colour stood proudly against his standard khaki tunic, a salute to the 2nd Infantry Battalion in the war before his. For many casual observers, Frank was just a black man fighting in a white man’s army. To Frank and his battalion, the Iris purple on mint julep green, the silver stitched border of the second Australian Imperial Force were the only colours that meant anything. Three colours that joined men irrespective of their skin.

During his first two years of service in the Australian Imperial Forces, Frank trained in Palestine and served in Benghazi, Greece and Crete, before fighting in Libya and the battle of Bardia and becoming one of the legendary rats of Tobruk. For two years Frank saw parts of the world he had never heard of, all the while dreaming of the land of his ancestors and his family’s home. Frank returned home on the 4th of August, 1942 aboard the SS Canterbury, after days spent sailing the choppy Indian Ocean, the sight of the Australian coastline was a welcome sight and the soldiers’ throats began to burn with emotion. A marching band met them at the dock in Port Melbourne, the cheers of soldiers and loved ones bounced off of each other. Frank swaggered home to his family in a clean uniform and with a freshly shaven face. He was back on his soil and he would soak up every minute until he had to be deployed again in one month’s time. Frank’s next stop: Papua New Guinea.

The Kokoda Trail is perhaps one of the most infamous battlefields in Australian wartime history. Stretching for 96 kilometres across the mountain ridges and forest gullies of the Owen Stanley Ridge in Papua New Guinea. The punishing trek that runs from the south-western point of Owers Corner in Central Province to the north and the village of Kokoda in Oro Province. Soldiers climbed through dense foliage over mountains and down ravines in the hopes of resisting an advance by the Japanese Army through the pacific nations.

Private Frank Richard Archibald and his fellow soldiers in the 2/2nd A.I.F. Battalion arrived on the shores of Port Moresby on the 21st of September, 1942. The lapis lazuli water sparkled in deep contrast to the lush green forest which obscured the rolling hills – a picture of paradise on the cover of an unimaginable hell. ANZAC troops had fallen back to Imita Ridge following the battles of Isurava and Brigade Hill, Frank’s battalion was sent in to reinforce Australia’s defence line and protect the right flank of the Moresby area. Their mission: to hold their ground or die trying.

Kokoda was unlike any other battlefield in the Second World War. The oppressive heat bore down on soldiers’ backs, a further weight added to their already heavy rucksacks. The air was cloaked in a thick humidity that stuck to the back of their necks and had them dreaming of desert territories – what they wouldn’t give to spend just one day in total dryness. Mountains that defied all physical strength and trails cut merely three feet wide through tangles of wild vines and prickled plants. Descending faces of mountains for days one end and constantly keeping their knees bent and at a lean to balance their way down left the men with “laughing knees.” Their legs would shake and their knees knocked together as the steep terrain jarred their joints, making it hard to keep their rucksacks from slamming to the damp forest floor.

*****

The battles were a far cry from the conflicts they fought in the Middle East and Europe in the battalions first two years in the war. The eerie silence of the mountain, occasionally broken by the deep-throated cooing of the local birds, would leave men on edge, hearing false footsteps and imaginary gun clicks. Every now and then they would pass dead bodies or piles of fouling and rotting food, the smell of dank soil fighting with the fetid stench of decomposing corpses. Their hearts would flutter rapidly and their breath would rattle in their chests as they waited for any sudden attack by the Japanese. When those attacks came, the roar of gunfire and screams of men would echo against the walls of the mountains. Men would fight one on one or in small groups, their swift attacks and brutal violence would come to define the nightmare that was the conflict on the Kokoda Track.

Private Frank Richard Archibald fell victim to this vicious violence on the 24th of November 1942. His battalion was in the process of securing Sanananda when they crossed the path of a group of Japanese soldiers manning machine guns. The Japanese soldiers had dug themselves in along the fire track which the ANZACs were using in their march – a vantage point that gave a clear shot of Australian soldiers. Under intense fire, the commander made the decision to split the platoon up, leaving one group behind to engage the enemy while the rest of the platoon moved beyond. Frank was a part of the group left behind to protect the others. The harsh crack of machine gun fire and the smoking smell of gun powder surrounded Frank as he fought valiantly against the foe. Frank soon noticed a friend who was caught in a highly dangerous position, and without a second thought rushed to his aid. Frank was recovering his friend when he fell into the line of a Japanese machine gun. Private Frank Richard Archibald gave his life for his country and for his fellow man – a true embodiment of the ANZAC spirit.

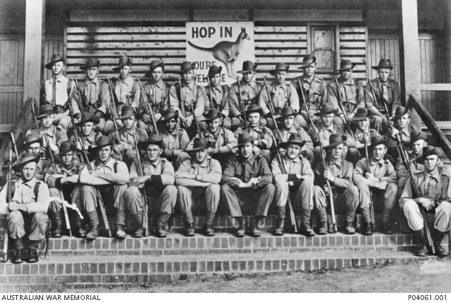

Private Frank Richard Archibald (pictured in the second row, fourth from the left) served as part of the 2/2nd Australian Infantry Battalion in World War II. Photo courtesy of the Australian War Memorial.

*****

The Commonwealth War Gravesite, Bomana Cemetery, sits in the final stage of the Kokoda trail in Port Moresby. Sitting high on the hillside, 3069 of our known and 237 of our unknown ANZACs and 443 Allied soldiers, sailors and airmen rest in their graves looking over the never-ending valley of green, a picture reserved for the martyrs of the war in the Pacific. Low-lying clouds hover over the mountainside, a mist of ghosts who lived and died beneath its trees. There’s a stillness, a quiet song that falls over the gravestones, a final peace for soldiers who knew little more than the hate-filled sounds of gunfire. This is such a stark contrast to the man-manufactured horrors faced by these soldiers on the Kokoda Trail and the ethereal natural landscape in which these men rest. Between the rows of white marble headstones lies the heartbreak of mothers, Australia’s brave sons asleep in the bosom of another nation. It is here, between the Cross of Sacrifice and the Stone of Remembrance, that Private Frank Richard Archibald lies amongst friends in a King’s garden.

For 70 years, Frank’s soul was in a state of unrest as it is trapped in a limbo between his body’s final resting place and his spiritual homeland in the Gumbaynggirr nation.

“Its somethin’ that yeh can’t explain,” says Uncle Richard, Frank’s cousin.

“An’ it’s inside of yeh body an’ at the moment just pure emotional, it’s just somethin’ yeh can’t, it’s a big thing for the Archibald family.”

*****

It’s ANZAC Day in 2012 and a pulsing didgeridoo plays the sounds of Gumbaynggirr country through the white stone garden of the Commonwealth’s martyrs. Lying between Private Gerald Joseph Wood and Private Noel Bevely Humphreys, his brothers-in-arms in life, and ultimately, in death, Private Frank Richard Archibald’s spirit is finally being laid to rest. Auntie Grace, Frank’s only surviving sibling stands side by side with Uncle Richard, as her wavering voice sings Old Folks at Home (Swanee River) for the brother she lost long ago.

“When I was playing with my brother

Happy was I

Oh, take me to my kind old mother

There let me live and die”

“Come back ‘ome to your family,” whispers Uncle Richard through the warming air of Port Moresby’s Bomana cemetery.

The Motuan-Koitabu people watch over the ceremony, sharing an understanding between their Indigenous culture and the experiences of the Archibald family as they bow their heads in respect. The descendants of “Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels” paying their respects and saying farewell to an ANZAC. Gumbaynggirr language man, Michael Jarrett, calls to the spirits as his tongue rolls steadily through the words of Frank’s people.

“We are not at rest while their spirits are not at rest on foreign soil,” a translator interprets the words for non-Indigenous ears.

“Today, after 70 years of restlessness and grief, we perform ceremony to heal that and bring closure to those families.”

As the words of Frank’s people are spoken over his grave, Gumbaynggirr elder, Uncle Martin Ballangarry, performs a ceremonial dance over the grave of Private Frank Richard Archibald. Dressed in a red loincloth and painted in white ochre, an acknowledgement of the connection to the land and mother nature, Uncle Martin kneels over Frank’s grave and sings over the clapping of his sticks, calling Frank’s spirit home.

Uncle Richard digs his hands into the damp, crumbling soil on Archibald’s grave, grasps a handful and places it inside a zip-lock bag to take back to Frank’s tribal land. Aunty Grace scatters a handful of Gumbaynggirr soil from an Australia Post mailing tube over the sprigs of rosemary growing from Frank’s resting place, stopping at times to roughly palm the tears from her face. Uncle Richard smooths over the soil as if smoothing over the charcoal hair of his cousin before repeating the gesture against Archibald’s name, colouring the white stone with the earth of his two homes. Aunty Grace presses the tips of her fingers to her mouth before sharing the kiss with the engraved lettering of her brother’s name – goodbye at last.

70 years after he died protecting his comrade, protecting his country, Archibald’s body was finally reunited with the soil of his ancestors and his soul is finally able to be reborn.

*****

We may not ever know exactly how many Indigenous soldiers laid their lives on the line for the protection of the Commonwealth in major conflicts dating back to the Boer War (1899 – 1902). Lack of documentation for Indigenous soldiers and a past refusal to acknowledge any service during the wars means that we don’t know who served, where they served and where they died. The numbers vary in each account but as far as historians can presume, between 700 and 1000 Indigenous soldiers fought in World War One, followed by the estimated 3,000 – 4,000 Aboriginal men and 850 Torres Strait Islander men who served in World War Two.

This year, for the first time in ANZAC Day’s 102 year history, Indigenous veterans lead the march down Anzac Parade in Canberra. With the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Referendum approaching, it is clear that Australia has come a long way in its relationship with the country’s first people. Yet, it is also vital to recognise that we still have a long way to go.

Lest we forget the sacrifices our ANZACs made on the battlefields of the world. Lest we forget the horrors and devastation that war brings not only to our homes but to the homes of others around the world, no matter what side of history they are on. Lest we forget the Indigenous soldiers who fought for a country that did not see them as citizens. Lest we forget the disrespect we showed to these men. We owe our respects to any man who risked their life for King and Country and died for his fellow man, regardless of his skin colour. Private Frank Richard Archibald’s honourable life and death remind us that whether we are black or white, we all bleed red.