Young Australians forced out of work by COVID-19 face the prospect of long-term unemployment as the pandemic halts economic growth.

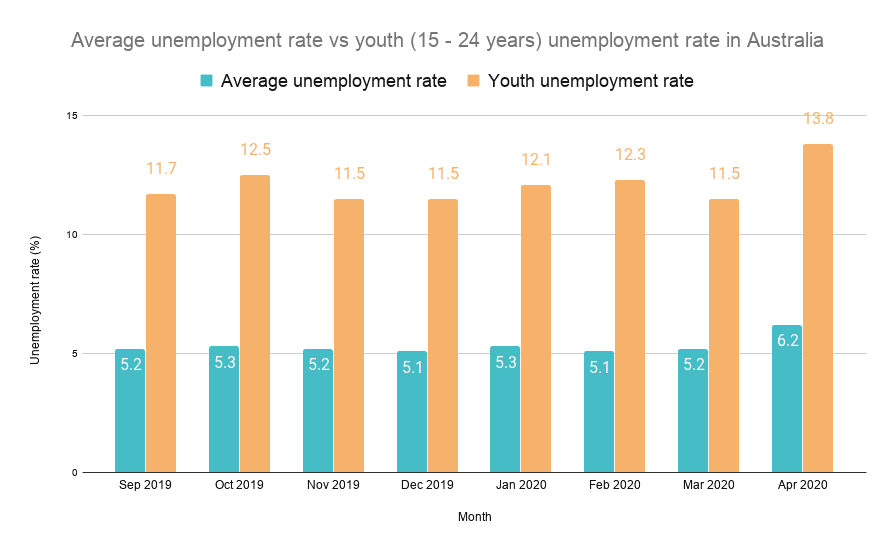

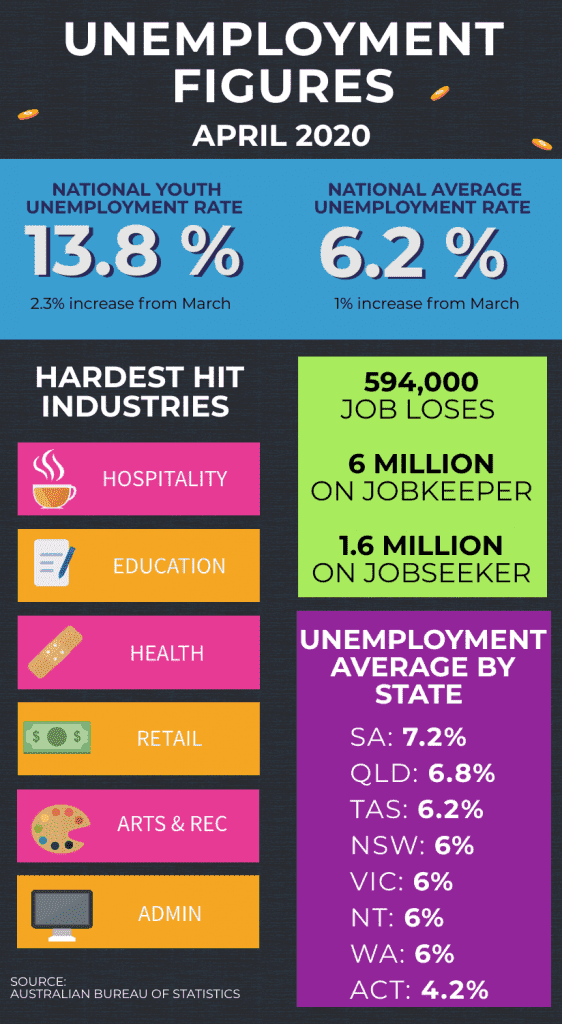

The latest figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) show youth unemployment (15-24 years) surged from 11.5 per cent in March to 13.8 per cent in April.

The national average unemployment rate jumped from 5.2 per cent to 6.2 per cent in the same one-month period.

Young Australians have been faring worse in unemployment since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008.

University of Melbourne economics professor, Jeff Borland said high youth unemployment stems from slower economic growth and the increasing employment of older Australians.

“Since the GFC we’ve seen a slow-down in the rate of growth in total employment, but at the same time labour force participation has continued to increase at about the same rate as before,” he said.

“What that means is there’s been an increasing gap between the amount of people who want to work and the amount of work that’s available, and young people are being crowded out by the older population.”

The youth unemployment rate rose sharply by 4.4 per cent following the GFC, spiking at 13.4 per cent in 2014.

Meanwhile, the national average unemployment rate rose by just 1.8 per cent in the same five-year period.

With current figures showing strong parallels with the GFC, Professor Borland warns COVID-19 pandemic could trigger another long-term spike in youth unemployment.

Young workers overrepresented in hardest-hit industries

“Already we’ve seen a negative effect on young people. Between March and April, young peoples’ hours of work fell by almost 25 per cent, 25 to 54-year-olds only about half of that,” Professor Borland said.

“I think the reason we’ve seen this really immediate impact is that young people are concentrated in industries which have been most adversely affected early on in the downturn.”

The latest ABS business survey revealed more than one-third of businesses reported reducing their staff work hours amid the pandemic across six industries: hospitality, education, health, retail, arts and recreation, and administrative and support services.

Three of those industries – hospitality, retail and arts and recreation – have the highest proportions of young people in their workforces.

Professor Borland said the downturn in economic growth is likely to have a big impact on recent, and soon to be graduate students.

“For young people who are finishing their education and graduating, they’re going to find it much more difficult than say last year’s group of finishing students to get into the labour market because there’s just going to be less jobs around,” he said

“That’s an effect that isn’t really being reflected in the numbers yet.”

‘You can’t put a figure on the emotional toll’

International graduate student Syed Mohammad spent four years studying his Masters in Accounting at the University of Wollongong and graduated at the end of last year.

The Pakistani national had been working casually at a service station and had just commenced a paid internship at an accounting company, a position he thought would eventually secure him a full-time job.

But, COVID-19 saw him lose both jobs within a matter of weeks.

“The accounting company moved to work from home, and according to them interns are not allowed to work from home, so I was made redundant there,” he said.

“Two weeks later, the owner of the servo told me the government won’t be paying JobKeeper for internationals, so he had to let me go.

Unable to access government financial support, Syed found himself struggling to stay afloat.

“It reduced my diet, and I couldn’t sleep peacefully knowing I had nothing to fall back on, not knowing what’s going to happen the next day,” he said.

“Working part-time, you barely save anything because living expenses are a lot here, so when you suddenly lose your income, there’s no cushion to fall back on but thankfully, [the government] realised and let internationals apply for an early release of our super.”

While there is no clear sign when he’ll find work again, Syed is not losing hope, applying for at least 10 jobs per day.

“The more you apply, the more chances you have of getting hired, so let’s see how it goes,” he said.

“Most jobs now prefer people with permanent residency or citizenship, so the chances of getting a job are pretty bleak, but I’m not giving up.”

Speeding up job creation

Professor Borland believes the government needs to invest in job creation to limit the long-term impacts of the COVID-19 recession on young workers.

“The best thing for young people is that we get job creation going again as quickly as possible so then they’ve got jobs to move into,” he said.

He also wants to see additional education and training programs made available to young people who find themselves unemployed.

“It’s really important that we think of policies that are going to allow them to spend that time in a way that really puts them in the best position to get into work when job creation gets up and going again,” he said.

Summary of Australian Bureau of Statistics April 2020 unemployment figures.